A reader asks very pertinent Brexit questions:

Is the referendum we are having on 23rd June our only chance to leave the EU? In other words, if we voted to stay in this time, would we ever be able to, or have another opportunity to leave again?

There seems to be a lot of confusion and I believe the answer might lay in The Lisbon Treaty, article 50. But I have become bogged down with it and am struggling to find a definitive answer.

If our 23rd June vote is in reality our only chance to effectively escape, surely most sensible people would want to do so rather than be forever locked into it.

However, if this isn’t the only chance we will ever get, which risks us trying again later, surely the EU will try to legislate in a way that will make it much harder for us or any member to leave in future.

Here is some useful analysis from a blog featuring analysis of EU law (and with a UKinEU approach) – my emphasis added:

Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) was added to the Treaties by the Treaty of Lisbon. It confirms the possibility to leave the EU that many (but not all) legal observers believed existed beforehand. No fully-fledged Member State has in fact left the EU before or after the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, although some parts of Member States have done so.

Before the Treaty of Lisbon, this was accomplished by means of Treaty amendment (an amendment just to remove Greenland was ratified in the 1980s, and Algeria’s independence from France was finally recognised as part of Treaty amendments in the 1990s). After the Treaty of Lisbon, there’s a special procedure relating to small parts of Member States (or their associated territories) becoming less (or more) connected to the EU. But it doesn’t apply to entire Member States, or even to territories linked to the UK (the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man and Gibraltar).

So Article 50 confirms the possibility of Member States to leave the EU, and it is clearly the only legal route to leave, as a matter of EU law. There’s no possibility to throw a Member State out of the EU against its will, although its membership could be suspended if there are serious and continued breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law (Article 7 TEU). That clause has never been used to date either.

Read the whole thing, as it sensibly separates out what is legally possible from what is or is not politically and practically wise:

First of all, it’s sometimes suggested that that the UK could ignore the Article 50 process, and simply leave the EU without invoking that clause. As a matter of domestic law, that’s certainly correct. Our membership of the EU depends upon the European Communities Act, and Parliament could end that membership by repealing that Act.

But politically and economically speaking, this option is insane. It would leave many practical details of withdrawing from the EU unresolved, such as payments of EU funds to UK recipients …

More broadly, such a ‘unilateral declaration of independence’ would destroy the UK’s credibility as a negotiating partner with the remaining EU, and indeed with anyone else, given the clear contempt that it would display for the legal rules which the UK had previously accepted. It would be a long time before the UK could plausibly claim again that it had a record of ‘fair play’ in international negotiations.

What is this getting at?

The EU exists as it does because it is a network of treaties: contracts between states. It therefore falls under the definitive Vienna Convention, where this is the core rule in Article 54:

The termination of a treaty or the withdrawal of a party may take place:

(a) in conformity with the provisions of the treaty;

or

(b) at any time by consent of all the parties after consultation with the other contracting States.

In other words, and perhaps surprisingly, a state does not have the simple formal right unilaterally to proclaim that a treaty with another state is ended, and thereby end the treaty. Pacta sunt servanda: agreements are to be carried out (VC Article 26: Every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith).

In the EU’s case the parties (ie the member states) have all signed up to Article 50 that lays down a procedure for a state to leave on a negotiated basis. In theory it would be open to the UK to announce that it was leaving the EU and for all the other member states to agree forthwith without all the Article 50 process. But the Article 50 process makes sense – EU issues are now immensely complex so it’s wise to disentangle them in a measured controlled way according to procedures agreed by all.

A separate set of legal issues arises if the EU descends into such chaos or conflict that the UK (and maybe other member states) feel that the way is open to proclaim the treaties dead in the water so that the EU has effectively dissolved itself. In such circumstances the political and real-life disarray would be such as to force events to take their course, with lawyers happily wrangling over what exactly it all meant for a long time to come. Again, read the Vienna Convention for the formal position.

NB don’t forget that in all this it’s not enough to assert confidently what the legal position might be. It’s up to individual courts including in the UK to give a view when asked to do so in a specific case.

If the UK insisted that it had left the EU (eg by unilaterally asserting the sovereignty of parliament to repeal without more the relevant UK legislation), a huge legal mess would ensue if (a) the EU Court of Justice in Brussels insisted that the UK had not left the EU but (b) UK courts upheld the UK parliament’s decision. But that huge mess would have merely a walk-on role in a wider political collapse of confidence across Europe.

Now, let’s answer the specific exam questions.

Is the referendum we are having on 23rd June our only chance to leave the EU? In other words, if we voted to stay in this time, would we ever be able to, or have another opportunity to leave again?

No. It’s not our only chance.

TEU Article 50 seems to suggest that it is a one-way street, ie it launches a negotiation for a member state to leave the EU that ends with a negotiated deal giving that exit legal and political effect on the terms agreed. However, (of course) it’s formally possible that a state might launch an Article 50 process but along the way strike a new deal to stay on different terms. If all EU member states agree to those new terms in a new treaty or otherwise, life goes on accordingly.

If we vote against Brexit, we won’t trigger TEU Article 50, so it remains there ready to be used by us or by others as and when.

Plus events may eventually compel the EU to a massive treaty renegotiation in which the UK achieves a far looser arrangement than it has now or even a full departure (if that is what the UK government of the time wants and succeeds in getting agreed).

If our 23rd June vote is in reality our only chance to effectively escape, surely most sensible people would want to do so rather than be forever locked into it.

That’s a solid practical argument for Brexit if that’s how you see things. But it’s not a legal argument. And this is not our ‘only chance to escape’ (see below).

As we have seen in the UK’s case, these referenda come along only rarely. They are stressful and distracting, both for our system and for the rest of the EU. So if this UK referendum does not vote for Brexit, it’s hard to imagine a new referendum any time soon.

That said, you never know. And ‘forever’ is a long time in politics:

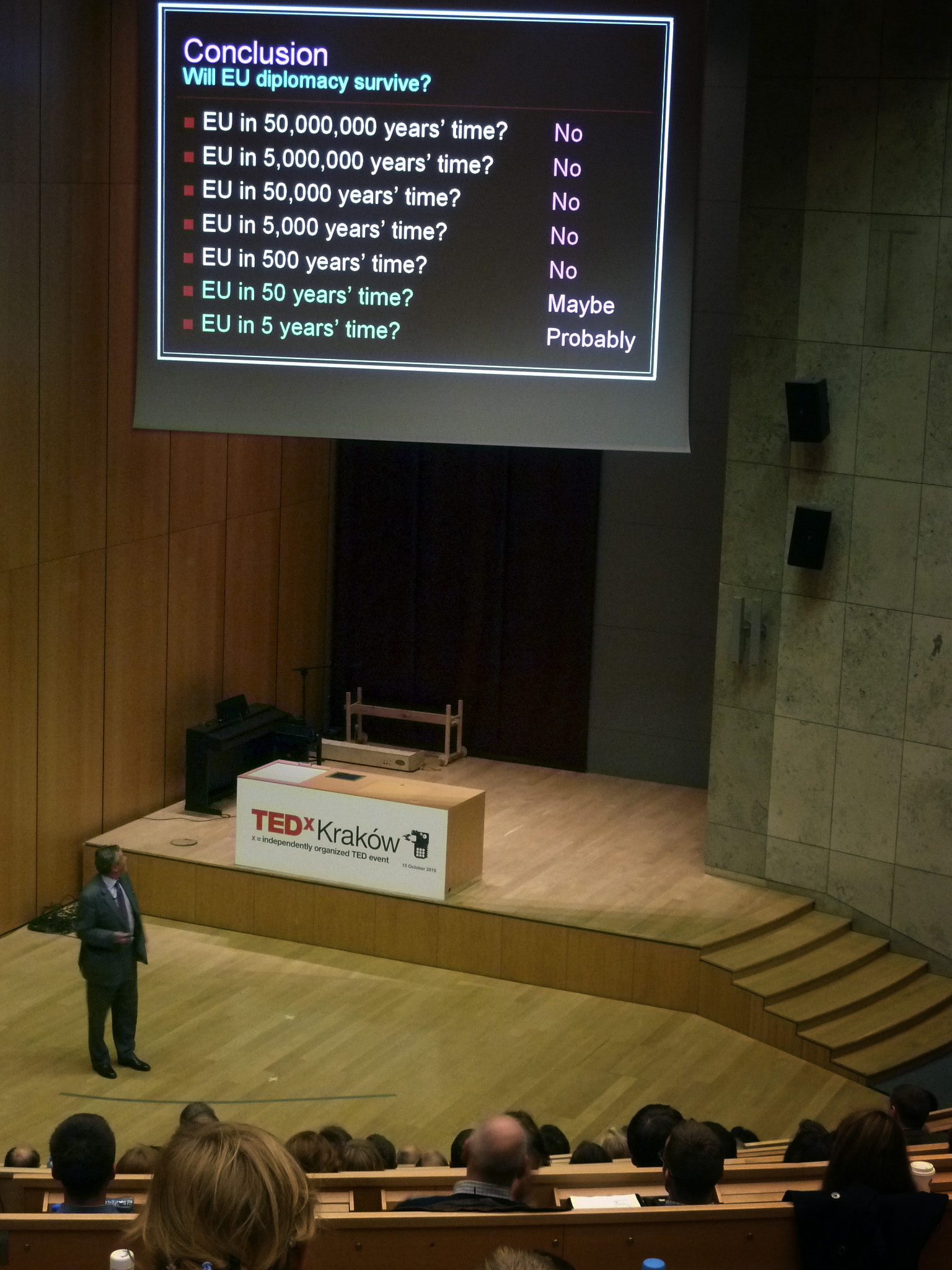

This is a youthful me me at at TEDx Krakow in 2010 talking about the Physics of Diplomacy. Watch my talk here:

However, if this isn’t the only chance we will ever get, which risks us trying again later, surely the EU will try to legislate in a way that will make it much harder for us or any member to leave in future.

Don’t panic. The ‘EU’ for this purpose includes us, and we have a veto over any future treaty change. In practice all member states quite like having this escape hatch in the treaties – why give it up?

TEU Article 50 and its EU exit procedures MIGHT be abolished in any future wholesale EU treaty renegotiation! BUT that that happens ONLY if no member state vetoes its abolition. So the UK (or any other member state) can stop a majority of EU member states ‘repealing’ TEU Article 50 – if that is what the UK (or any other member state) at the time wants to do.

Bottom Line?

Don’t confuse the formal legal position(s) and learned squabbles over what they mean with Real Life.

All the EU’s treaties and rules can be changed overnight if things reach such a drastic pass that all EU member states agree that that is the best outcome.

In political and practical terms, it looks safe to assume that if the UK votes for UKinEU, that will stay the position for a good couple of decades UNLESS wider events compel some fundamental rearranging of ‘European architecture’ in the meantime.

In such weighty if not dangerous circumstances, EITHER the UK negotiates a new deal up to and including Brexit, OR the EU effectively disintegrates to the point that the authority of EU law and/or the willingness of member states to pay into the central EU pot fall away.

If UK public opinion despite a UKinEU vote soon thereafter moves into panic mode about events elsewhere in the EU, a UK government desperate to keep control might decide to activate TEU Article 50 without a referendum, or otherwise seek to persuade EU partners to let the UK leave forthwith (ie ending our treaty role by mutual agreement as per the Vienna Convention).

Again, that would be part of dramatic wider European political convulsions/collapse. It would create a completely new situation of unfathomable complexity if not danger. But in my view it can not be ruled out.

Sooner or later, things end. Including the EU in its current form and/or the UK’s membership of it. That’s just the way it goes. And these days things move far faster and more unpredictably than anyone can imagine or control.

The only issue is how best if at all to manage that process as and when it finally arrives. Then, if anything is still standing, rework the law to reflect the new realities.

Hi.

suppose BREXIT won,after that what will happen to free movement of persons,we are planning to settle in UK in august so very confusion situation is,

we can simply do as switzerland has done, and inform the world that we will accept the visa of the Schengen area, but that we will still be running security and passport checks at our own discretion. switzerland has been doing this for many many years now, and it is a perfectly acceptable idea, that offers the best of both worlds, freedom of movement for legalised persons, and security against illegal persons. however, if you are not in an EU country at present, it is far more difficult to settle into Britain, due to us having a quota of migrant EU citizens we are forced to fill be the EU. this means that if we leave, we can choose to let in better educated people from everywhere globally, who we want in the country, and deny access to those we do not want. i hope this helps you, sorry it's so late as a reply