Back in 2010 when I was young and optimistic and had more time than nowadays, I poured out work for a website called Business and Politics. That site has vanished, as sites do. So my work is no longer accessible. But some of the pieces are still a jolly romp to read today.

See eg this one, on the lessons about basic economic principles to be drawn from children’s books:

Over at always terrific Browser is a link to an excellent idea, namely thoughtful people talking about five particularly good books on a given theme. This one caught my eye: Yana van der Meulen Rodgers of Rutgers University giving us five books which, she says, each teach important lessons of economics to young children. In fact she has worked up a much longer list of such books as part of her university work, of which these five are only a small proportion. So far so good.

Yet somehow my heart sank when I looked at her descriptions of the five books in question. Basically, they appear to be propaganda tracts for different varieties of political correctness.

Here’s a sample, Cloud Tree Monkeys:

This book focuses on a woman who is very poor. She is in a South Asian country and she picks tea-leaves for a living. Her daughter is either too young to go to school or they cannot afford to send her to school, so the daughter often comes along to the plantation. But one day the mother gets very sick and she can no longer pick tea. The daughter is worried that there is no money to pay for the doctor, she really despairs, and ultimately ends up dragging this enormous tea basket to the plantation to try and do the work herself. The overseer is really an angry, mean boss, and he just laughs at her.

The perfect combination. A poor “non-white” woman worker on a tea plantation, with a daughter being oppressed by an angry, mean male boss. Luckily magic monkeys help the daughter pick tea when the mother gets sick. The Emperor loves the tea and sends a bag of gold coins to the family. Hurrah! This book is said to have the great virtue of teaching children about “income inequality”. But the message about economics seems hopeless, de-linking hard work from beneficial outcomes: we can all get rich, as long as the magic monkeys feel sorry for us and do our work for us – we are helpless victims! A pernicious economics message to teach children, if you ask me.

Anyway, you get the idea of Yana van der Meulen Rodgers’ general approach to key economics messages. It got me thinking: which five children’s books would I recommend to Business and Politics readers as giving central economics messages for life? What actually might those messages be?

Here is my list. It is chosen to be politically incorrect: politically incorrect (and therefore harsh and realistic) messages tend to catch the imagination of children by compelling them to think about (a) the difference between Right and Wrong, and (b) why Wrong decisions should and often do lead to Bad outcomes. Because simple morality is at the heart of economics and business, or at least it should be.

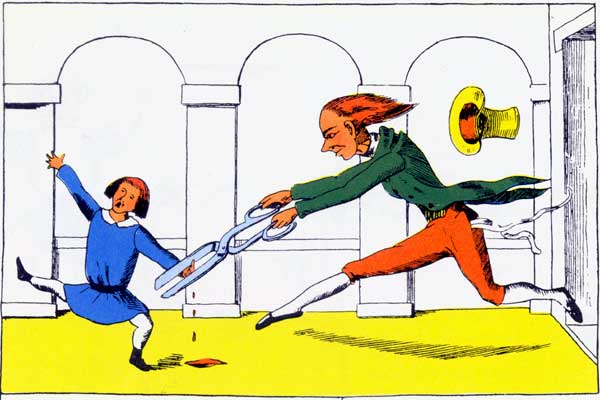

First, the all-time classic Struwwelpeter. This is a strange, wonderful book coming to us deep from 19th century German bourgeois neurosis, and all the better for that. It comprises a series of stark moral ‘cautionary tales’ made all the more ghastly by stunning illustrations: the Long-Legged Scissorman races in to cut off the thumbs of stupid Little Suck-a-Thumb who ignored his Mama’s warning and kept sucking his thumbs. Blood even spurts out in the best tradition of contemporary rubbish horror movies.

See also the fate of Pauline who disobediently plays with matches and is burned to cinders, leaving the wise cats to weep profusely on the ashes.There is a modern ‘diversity’ angle of sorts, where three horrid pale-skinned boys are dipped in black ink as a punishment for teasing a brown-skinned boy who has a frilly umbrella.

An unambiguously excellent book. Key economics messages? Be smart. Obey instructions from a reasonable authority. Don’t play with fire (ie keep up a good standard of Health and Safety in the workplace). Don’t walk around with your eyes looking only at the sky, or you’ll fall into the river and the fish will laugh at you: be ambitious – but realistic.

Second, Five Children and It. This is the classic book by E. Nesbit. Five very middle-class ‘white’ English children go on holiday and unearth a mysterious, grumpy creature which makes their wishes come true. Each wish seems very reasonable at the time, but in each case it all goes horribly wrong.

The story has all sorts of long-lost ‘class’ overtones (cooks and house-maids, uncomfortable proper clothing, rough tradesman and so on), a history lesson in itself. Each episode is beautifully turned. Not least the one where the children wish for and get an unlimited amount of gold coins, then find that this supposed wealth does them no good at all.

Key economics messages? Think ahead. Treat your staff well — being bossy or patronising doesn’t work. Don’t be impressed by the prospect of getting rich quick, as there is likely to be a serious snag.

Third, Fireman Sam’s Book of Colours. I suspect that this appalling tome is out of print. If so, good. It had no story, indeed no words — just different pictures of the smug Fireman Sam going about his tedious work in a way intended to teach young children their colours. On one page there is there is at least a hint of drama, namely a bright orange fire in a farm barn which Fireman Sam duly extinguishes. He then sits down for a picnic with his cat.

You may well find your two-year-old son wanting you to read to him this unspeakably boring book 2000 times. If you do manage to survive this ordeal, 16 years later you will have the pleasure of taking him to Cambridge for his Physics application interview. In other words, it teaches parents (not children) the key economics message of Persistence. And firm fire-safety standards.

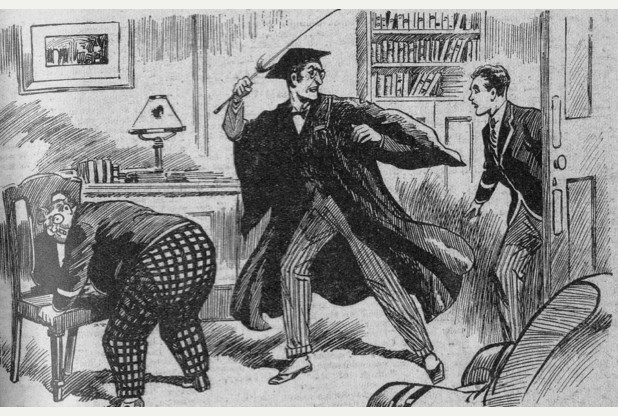

Fourth, Bunter the Ventriloquist. The Billy Bunter books transport us to a distant world of plucky boys at a TV-free minor English public school: struggling through Latin ‘con’, oblivious of girls and sex, preoccupied with footer, fair play and tuck. In this fervid setting the main character is Billy Bunter, a lazy, dim and dishonest but above all fat schoolboy whose only ambition is to pinch tuck from other boys (preferably when they are playing footer) and/or have a nap. His attempts to achieve this almost always lead to negative outcomes, such as a severe whopping from the cane of gimlet-eyed form-master Mr Quelch. Yarooh!

These Bunter stories were famously produced on a prodigious scale by Charles Hamilton (writing as Frank Richards) for the long-lost genre of Boys Weeklies, so beautifully described by George Orwell. If you have not read his brilliant essay on the subject, stop what you are doing and read it now.

I found them splendid material for reading to our young children (two boys, one girl) as each chapter briefly reminds the reader about the story so far. The stories are wittily written in a curiously attractive repetitive style. Billy Bunter is not only generally fat, as it were. He has fat eyes, fat spectacles and a fat imagination. Again, there is an interesting “diversity” angle as one of the key schoolboy heroes is an Indian, Hurree Jamset Ram Singh nicknamed Inky, who talks in an inimitably convoluted way: “The fat-headedness of this caper is truly ridiculous, or as the English proverb remarks “The bird in the hand looks before it leaps”, my esteemed execrable Bunter”.

In this one outstanding story Bunter somehow learns to become a skilled ventriloquist. He uses his new-found powers to play tricks on the other boys so that he can pinch their tuck. After being punished by the schoolmasters for his misdeeds he plays tricks on them too, including by ordering bags of coal and potatoes and the number of inflated balloons to be delivered to Mr Quelch in the classroom. This scene is one of the finest and funniest in English literature, the usually steely middle-class schoolmaster being reduced to shrieking when the earthy working-class tradesman refuses to take the absurd items away. It all ends badly for Bunter, of course, with a drastic caning which leaves the dolorous Fat Owl reluctant to use his ventriloquist powers ever again. Yarooh!

Key economics messages? Don’t over-consume: use resources sparingly. Look out for negative externalities, ie inadvertently creating costs for other people through your own actions. Be honest — do not steal others’ tuck. If you’re selling things by telephone or Internet ordering, have in place robust precautions to be sure that the person making the purchase is duly authorised to do so.

Finally, Daddy, Will You Play With Me? by Harriet Ziefert and Emily Boon.

This is an interesting one, as (under the pressures of political correctness?) the title seemingly has mutated in recent years into Grandpa, Will You Play with Me? In this story Little Hippo keeps asking Daddy/Grandpa to play with him, only to be fobbed off with various highly realistic Daddy-like excuses (ie Daddy is reading the newspaper, polishing the car or ‘ working’). In the end they sit down together to snuggle up and read a book.

Key economics messages? Take good care of expensive capital assets such as vehicles. Balance your time sensibly between work and family. Look out for the opportunity cost of being too focused on what you are doing. Don’t take no for an answer.

All absolutely fine stuff.

An interesting and characteristically eclectic selection, Charles, not least the Bunter which I remember well but wouldn't have expected to see in an economics reading list. Did you ever come across Dr Seuss's Thidwick the Big-hearted Moose?