It’s hard to say which was the most painful moment of the Funeral of HM The Queen.

The TV images during the day were exquisitely done – almost every shot a startling combination of colours and unexpected focus.

But for me the small extended procession along a quiet country road and then up the Long Walk to Windsor Castle was especially hard to watch. It was as if the coffin and the small accompanying soldiers were floating through the English countryside. Then every minute the thud of a cannon, followed a few seconds later by a single peal of a bell. Unrelenting. Remorseless. Yet so beautiful.

And then, finally, to end the Committal ceremony in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, King Charles laid the small Queen’s Company Camp Colour of the Grenadier Guards on the coffin. That miniature flag stays with the Commander.

The new national anthem played and was sung, measured and strong: God Save the King. Yes, the pageantry has been moving and spectacular. But this is also a key moment of State business. Our new Monarch King Charles III assumes responsibility.

* * * * *

Here’s my piece for DIPLOMAT magazine on my own encounters with HM The Queen:

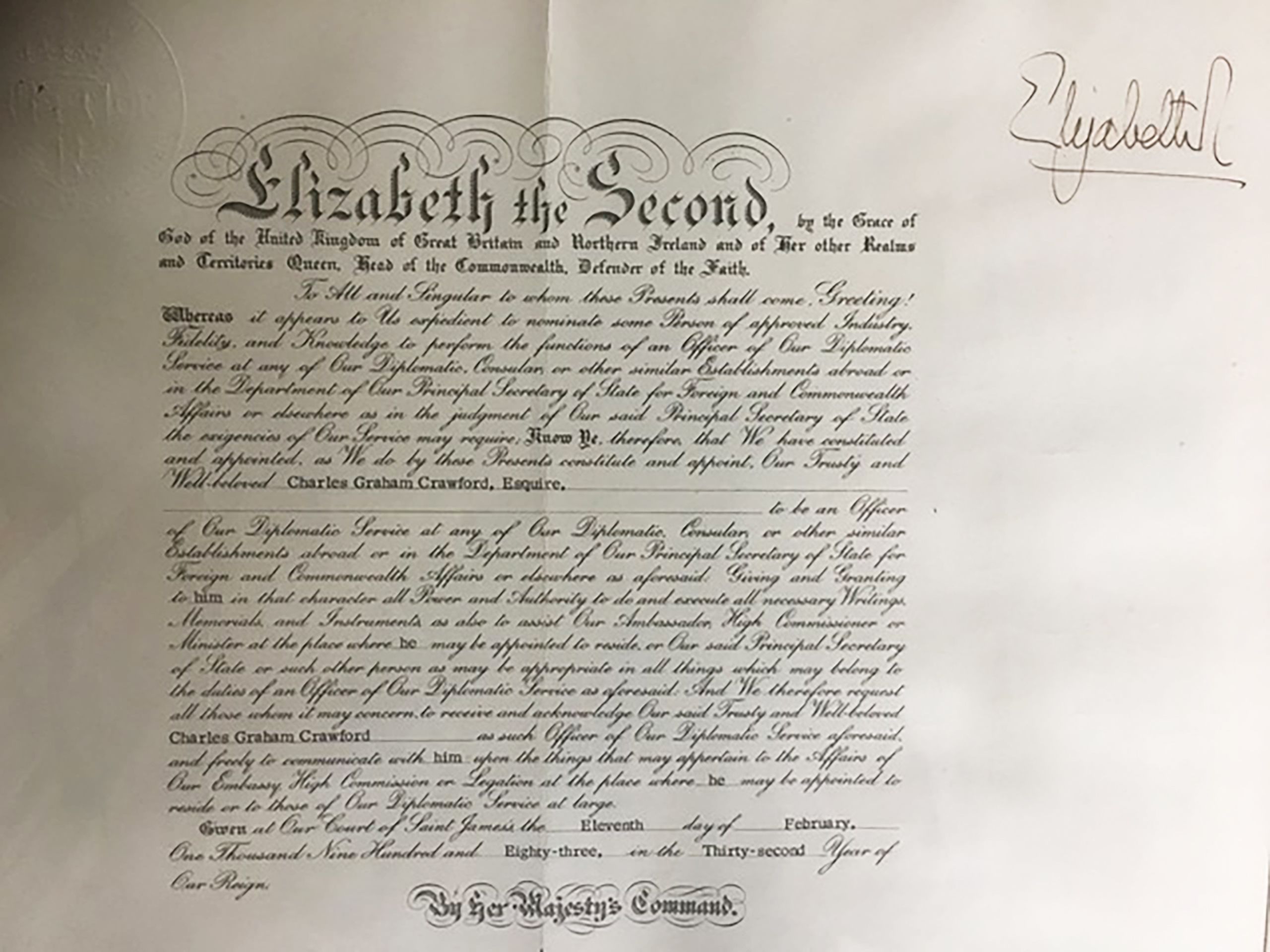

After that first short London role I move to Yugoslavia as Press Attaché. I demonstrate Industry, Fidelity and Knowledge in no small quantities. In 1983 The Queen signs my formal appointment as an Officer of her Diplomatic Service:

I help organise the State Visit to Moscow in 1994:

The public highlight of the visit is a ballet performance at the Bolshoi Theatre. Before the performance starts all our eyes are on the main box. The Queen and President Yeltsin appear. The Queen wears a dazzling blue-green jacket and sparkling tiara. Thunderous applause. A warm wonderful moment of high political symbolism.

President Yeltsin hosts The Queen for a Kremlin Banquet: the first black-tie event there since the Russian Revolution? Word has that the Russian guests have been scurrying round Moscow theatre costume warehouses to find suitable capitalist dinner jackets for the occasion.

John Sawers (later head of MI6) is there supporting Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd. We’d served together as First Secretaries in South Africa. I sagely opine that if in Pretoria in 1988 I’d told him that a mere 300 weeks later both apartheid and the Soviet Union would have collapsed and that we’d be sitting in the Kremlin with The Queen listening to a Russian army brass band play Engelbert Humperdinck’s greatest hits, he might not have believed me…

I rise to the giddy heights of Ambassador in successively Sarajevo, Belgrade and Warsaw. There is a tradition that each UK Ambassador or High Commissioner plus spouse / partner meets The Queen once during that posting. Mrs C and I duly visit Buckingham Palace three times.

By this point in her reign, she is greeting these diplomatic couples in small groups. We’re ushered into a smaller chamber with some elegant courtiers. The Queen arrives and spends a few minutes with each couple in turn. She’s been on the throne for over 40 years: she has plenty of astute things to ask and say about our respective postings.

As one of these gatherings is concluding, The Queen blandly sums up, noting that we are all off to most interesting places. I reply that my colleague who is heading to Georgia will have much the best of it:

“I visited Georgia to help set up our first Embassy there. We had a dinner of spicy stew in Georgia’s best restaurant. A huge rat ran down the side of the wall past our table.”

The Queen looks at me as if I’m insane. Then she bursts into much Royal Laughter.

How to sum it all up?

The Queen’s reign ends. King Charles III ascends the throne. Our state ceremonies are unfolding in that uniquely British royal style: solemn, graceful, superbly organised yet somehow also gentle and human.

Is any hereditary monarchy fair? Democratic? Modern? No. But those questions assume the wrong starting-point for thinking about core national values.

Think about the Stone of Scone that has been part of the coronation ceremony for Scottish and British monarchs for well over one thousand years. Ponder what that profound dignified continuity tells us about ourselves, and where we’ve come from. And what politics in so many other divided countries might be like if they had some of that unifying tradition.

Ponder too the moral significance of the fact that each week the Prime Minister of our country has a private audience with the Monarch: a moment each week for our most senior political leader to reflect on where his or her policies fit in with that continuity and tradition.

As the late Roger Scruton put it so well, “The constitutional monarchy is the light above politics”.