Readers’ whose brains glaze over when trying to work out the acronymic difference between the European Union, the European Economic Area (EEA) and the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) may find this piece over at the Adam Smith Institute helpful (h/t Roland Smith).

It looks at the Big Picture (emphasis in italics added):

It was in the early 1990s that the world changed dramatically with the collapse of Communist federations and emergence of new nations; the opening up of China; the launch of the World Trade Organisation; the opening up and commercialisation of the world wide web; and the coming of environmental politics.

As well as opening global trade to a much greater degree than we had known before, law and standards-making correspondingly moved upwards to the global level. Countries of the world now participate in rule-making at the global top table. EU member states can do this but their voice is often muffled by the ‘common position’ of a European Union still driving towards statehood.

The way trade now works is less about tariffs as it is the removal of technical barriers to trade and harmonisation of systems, where virtually every nation on earth outside the EU has a direct line to the real top table in order to set and shape the agenda.

That makes the EU stick out like the 1950s anachronism that it is: Taking laws from the global level and passing them to its members while also constraining its members’ voices and their freedom to act on their own account in the wider world. As for the argument that the EU’s size gives us greater clout on the world stage, the EU’s inertia more than cancels that out. That slows to a crawl its ability to operate at global level or strike trade deals on our behalf – it moves only as quickly and as far as its most protectionist member state.

No other bloc seeks political union – the creation of a new country – and the normal state of affairs is for self-governing nations to cooperate with each other and at global level. No other country or region of the world has any intention of following the EU model.

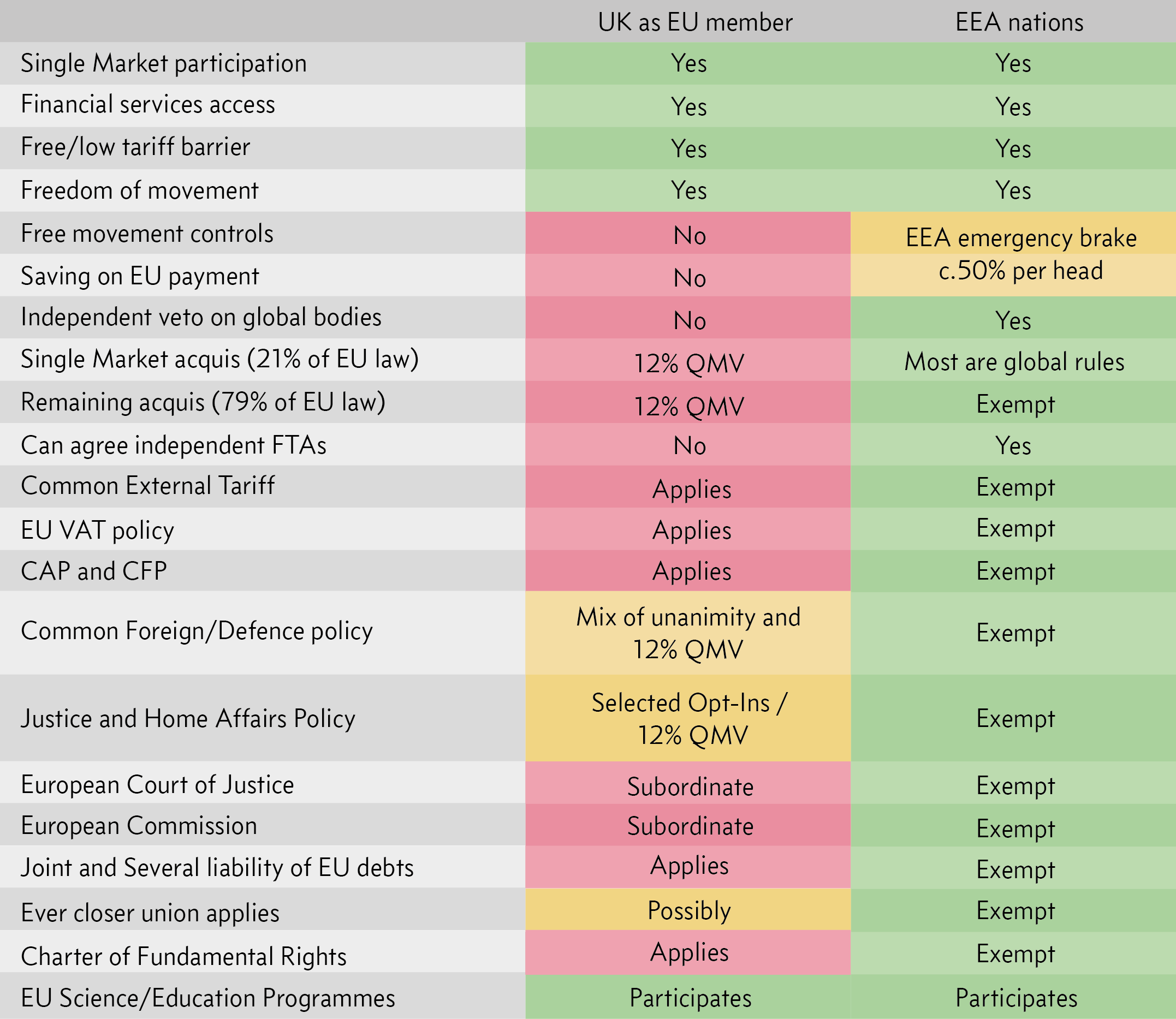

And, it has a handy chart summarising the differences between being in the EU and being in the EEA:

No doubt all sorts of clever glosses can be added, and qualifications made. But there are ways in which the UK can stay close to its European and particularly EU partners without being in the heavy, undemocratic EU framework.

Allister Heath now agrees:

It is desperately important that the economic case for Brexit be made much more vigorously. It needs to be divided into two components: a takedown of the EU as an ultimately doomed, job-destroying, declining and mismanaged behemoth which stands no chance in an increasingly agile, globalised world; and the mapping out of a clear exit strategy, compatible with Leave’s objectives, that shows how we would maintain and enhance our openness to the world.

The message must be clear: we would be better off out – in terms of jobs, wages and growth. The costs of leaving will be smaller than the benefits, and this would become evident within a few years of leaving.

The core assumption of the anti-Brexit economists is that leaving would erect damaging barriers to trade; the pro-Brexit side must take on and demolish these arguments.

The good news is that it’s quite easy to do so. The Leave campaign’s long-term aim is to break away completely from the EU. But there is no doubt that, were we to vote Leave on June 23, the UK would seek to adopt, as an interim solution, a Norwegian-style relationship with the EU which ensures that we remain in the single market, giving us plenty of time to work out new arrangements with the rest of the world.

That is both the only realistic way we would quit the EU – the only model, that, plausibly, MPs would support as a cross-party compromise deal – and the best possible way for us to do it. The Norwegians would welcome us with open arms, as their own influence would be enhanced, and other EU nations would seek to join us. Such a deal would eliminate most of the costs of leaving, while delivering a hefty dose of benefits as a down payment…

Read the whole thing.

One other big point.

As mentioned in the Adam Smith piece above, a large amount of the technical rules that make globalisation happen (including this blog post and myriad other things) emerge from international processes of different shapes and sizes negotiated at the world level. The EU often merely organises these ‘external’ rules for EU Single market purposes.

By leaving the EU the UK would be back once again as a heavyweight independent voice in many of these technical but strategically important international deliberations and decisions. Yes, we would lose influence in EU Single market deliberations where decisions affecting us are taken. But in return we’d regain strategic influence higher up the global policy chain. Not a bad deal?

In short? Brexit towards the EEA represents a massive positive step (and the only possible step) towards building a smarter, light-touch Europe.

My brain tends to glaze over trying to work out just about any acronym. 😉 It is interesting how the whole Brexit thing is playing out. Wonder how 2017 will go with everything else that has happened since Brexit.