I head towards the end of my Master’s degree programme with University of Buckingham. My paper will be on What is Chess?

The problem with philosophy is that one issue drifts inexorably into another and it’s next to impossible to write something self-contained that is not either hugely over-detailed (boring) or just trivial. So as I at least know something about chess, and as Wittgenstein and many others have used chess to illustrate philosophical points, why not go there?

Thus:

Chess has the feature of what looks like infinite variety for human purposes, yet it is in principle finite.

The number of possible positions of chess pieces on a chess board can be calculated in different ways, but that number is always large beyond imagination. In 1950 Claude Shannon argued that it was at least 10120. Back then a chess computer programmed to play a perfect game of chess would be kept busy:

A machine operating at the rate of one variation per micro-second would require over 1090 years to calculate the first move!

That number of possible positions (hereinafter the Shannon Number or SN) is finite. It’s possible to reach the end of a list of them, even allowing for myriad positions that look identical but in chess terms are not identical.

The SN list of possible positions of chess pieces can be organised in different categories that are not mutually exclusive:

- Positions that include or can be reached from the original ‘legal’ starting position of the pieces

- Positions involving illegal starting positions of the pieces

- Positions not permitted by the laws of the game (eg where the two Kings are on adjacent squares, or both Kings are in check)

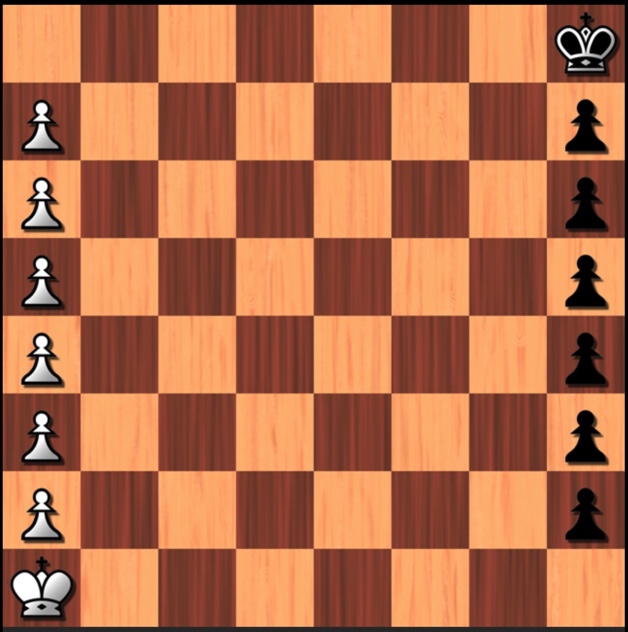

- Positions that in principle cannot be reached from the legal starting position of the pieces, such as this one:

This position is not ‘illegal’ under the laws of chess but it is impossible to reach under those laws: it requires each side to have made 15 pawn captures, and each side has too many pawns on the board for that to have happened.

But even after trillions and trillions of such positions are ignored as not a legal or possible part of ‘chess proper’, far more distinct legal positions remain available. It is obvious that by simply making the board 9 x 9 squares and introducing a new piece (say a Duke) that combines the range of Rook and Knight as a Queen combines the range of Rook and Bishop, another staggeringly larger yet still finite number of positions would be created.

Thus another reason for finding chess a source of philosophical contemplation: what are its rules and their limits? Where does chess ‘stop’ and something that is not-chess (eg another game) begin? How to tell when one is crossing that border?

Wittgenstein poses a question:

But isn’t chess defined by its rules? And how are these rules present in the mind of the person who is intending to play chess?

It is not straightforward to be completely certain what the ‘rules of chess’ are, and what they cover. The official FIDE Laws of Chess for tournament chess themselves include procedures for an arbiter to decide what happens if a novel situation arises that is not covered by the laws and the agreed tournament code.

Few if any chess-players know every single rule in the latest version of the FIDE Laws of Chess. And to add even more complications, under those Laws even illegal moves may not stay illegal if they are not immediately noticed by the players or arbiter.

John Searle has developed a distinction between ‘regulative’ and constitutive rules:

Examples of the distinction are easy to come by. So, for example, the so-called “rule of the road”, according to which people in the United States drive on the right hand side of the road is a regulative rule. Why? Because the activity of driving exists independently of this rule; the rule regulates an antecedently existing activity.

The rules of chess, on the other hand, do not just regulate, but they constitute the activity they regulate. So, the rule that says the King moves to any adjacent square, one square at a time, looks like a regulative rule, but in fact taken as part of the whole system it is one of the rules that in their totality constitute the game of chess. If you do not follow these rules, or at least a sufficiently large subset of the rules, you are not playing chess.

So, question. How might one identify a ‘sufficiently large subset’ of chess rules to be sure that one is indeed playing chess?

That last idea of ‘constitutive’ rules is important and interesting. The rule creating the chess move called ‘castling’ involving King and Rook moving together in one move in a certain way (the only chess move of its sort) in itself creates ‘castling’. Without the rule there is no such thing. You can’t castle anywhere other than in a chess game, and by that very rule.

So, question. What rules or features of chess might be taken away without the chessness of chess being diminished? Are some rules necessary and sufficient for chess to be played, whereas other rules are (so to speak) marginal or inessential?

One example is the coloured chess-board. The official Laws of Chess, Article 2.1:

The chessboard is composed of an 8 x 8 grid of 64 equal squares alternately light (the ‘white’ squares) and dark (the ‘black’ squares).

The chessboard is placed between the players in such a way that the near corner square to the right of the player is white.

Nothing in the way chess is played turns on these colours. A game would be no different if it were played on a board of 64 squares that were all pale-coloured (although it might be rather harder in practice for players to spot diagonal Bishop moves).

But the number of squares is important. What if the game were played on a board of 10 x 10 but with the same pieces and merely added space for them to use? Or imagine an infinite board! How might that work? Welcome to Infinite Chess.

But … is that still chess? It’s definitely not draughts or tennis or CandyCrush. But is it still chess, or a version of it?

What does the idea of a version of chess mean? Is there a point at which one would have to say that the rules have been changed to such a point that it is no longer any version of chess – its chessness has vanished?

Ah. Philosophy. Just like Diplomacy. You always come back to borders…

Logging you in...

Logging you in... Loading IntenseDebate Comments...

Loading IntenseDebate Comments...